The Early History of Talking Machines

“The earliest speaking machines were perceived as the heretical works of magicians and thus as attempts to defy god. In the thirteenth century the philosopher Albertus Magnus is said to have created a head that could talk, only to see if destroyed by St. Thomas Aquinas, a former student of his, as an abomination. The English scientist-monk Roger Bacon seems to have produced one as well. That fakes were appearing in Europe in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries is shown by Miguel de Cervantes’s description of a head that spoke to Don Quixote -- with the help of a tube that led to the floor below. Like Magnus, this fictitious inventor also feared the judgment of religious authorities, though in his case he took it upon himself to destroy the heresy. By the eighteenth century science had started to shed its connection to magic, and the problem of artificial speech was taken up by inventors of a more mechanical bent.”

David Lindsay, “Talking Head”, Invention & Technology, Summer 1997, 57-63.

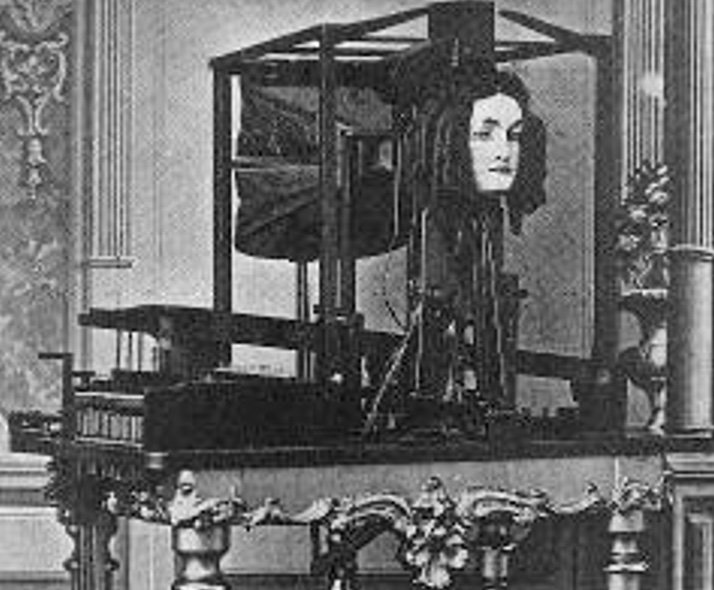

The Euphonia, Joseph Faber’s Amazing Talking Machine

Faber’s Euphonia

Faber’s Euphonia

About this device, David Lindsay (1997) writes:

It is “... a speech synthesizer variously known as the Euphonia and the Amazing Talking Machine. By pumping air with the bellows ... and manipulating a series of plates, chambers, and other apparatus (including an artificial tongue ... ), the operator could make it speak any European language. A German immigrant named Joseph Faber spent seventeen years perfecting the Euphonia, only to find when he was finished that few people cared.”

Political and social turmoil in the nation led to disruptions that impacted academics at Brandeis. I moved off campus to Porter Square in Cambridge. In addition to physics and biology, I was interested in computational modeling, mathematics, and statistical analysis. I requested, and received permission, to use the computing facilities at Harvard (in the punched card era), and continued to do most of my work there while still enrolled at Brandeis. I returned to campus at the start of my senior year, where I met my (then) future wife, Joette Katz, a freshman. We were married later that year. Finishing up my undergraduate career, I wrote an honors thesis on the relationship of Markovian models and finite state grammars. I received my BA in psychology and linguistics from Brandeis in 1971.

During the summer between my junior and senior years at Brandeis, I was able to get a position at what was then called the Rusk Institute for Rehabilitation Medicine (IRM) , in New York City (it is now called Rusk Rehabilitation, a part of NYU Langone Health ), working on analyzing data related to stroke patients. While there I met a consultant named Lou Gerstman, co-inventor, along with John Kelly, of the computer portrayed as HAL 9000 in the film 2001: A Space Odyssey. I mentioned to Lou that I had been reading a paper on aphasia by Donald Shankweiler and Katherine Safford Harris. Lou mentioned that he was also a part-time researcher at Haskins Laboratories (first in NYC and then New Haven), and that Shankweiler and Harris were both affiliated with Haskins, along with Philip Lieberman, Arthur Abramson, and others. Lou said that I should apply to graduate school at a university connected to Haskins, such as the University of Connecticut, Yale, or his program at CUNY. I did, but deciding to go to UConn because Joette still had a few more years ago and Storrs would end up being closer to Waltham than NYC.

The intellectual environment at UConn was outstanding, with a remarkable cohort of student and amazing faculty in both the psychology and linguistics departments. Some of my classmates included Steve Braddon, Carol Fowler, Diane Kewley-Port, Peter Kugler, Gary Kuhn, Claire Michaels, Terry Nearey, Robert Port, Tim Rand, Robert Remez, Jim Todd, Bill Warren, and many others. I received my PhD in experimental psychology in 1975 under the tutelage of Michael Turvey, Ignatius Mattingly, Philip Lieberman, and Alvin Liberman. After graduating I was an in assistant professor in psychology at UConn in the 1975-1976 year, and also commuting down to New Haven to do research and computer work at Haskins. My teaching load during this time included 10 course — 5 each semester, which these days would usually be considered onerous. It was not for me, and I decided to pursue a research career.

See, also:

My Career: Science, Research, Policy, and Ethics

Ethical Issues Related to Research and Emerging Technologies

White House Office of Science and Technology Policy

BioSketchList of Science and Policy RolesDownload CV as a PDF fileWikipedia pageHOME